This content is from the fall 2016 version of this course. Please go here for the most recent version.

Using Python Basics for R Users

Joshua G. Mausolf

October 24, 2016

Prerequisites:

If you have not already done so, you will need to properly install an Anaconda distribution of Python, following the installation instructions from the first week.

I would also recommend installing a friendly text editor for editing scripts such as Atom. Once installed, you can start a new script by simply typing in bash atom name_of_your_new_script. You can edit an existing script by using atom name_of_script. Alternatively, you may use a native text editor such as Vim, but this has a higher learning curve.

If you want to follow along, please clone the repository.

Outline:

- Ways of Interacting with Python

- Basic Data Analysis

- Function Basics from R to Python

Ways of Interacting with Python:

If you have properly installed Python, there are three primary methods of interaction with scripts and data analysis:

- The Shell

- Jupyter/IPython Notebooks

- Python Scripts

Coding with Python in the Shell

Overall, working in Python in the Shell can be simply initialized. Go to your shell, and type python. This will open a Python console (similar to the R console) where you can type code for simple calculations and testing.

The shell has many of the same limits as in R, namely having to type all your work and not being able to easily replicate your results.

In practice, I use the Shell version of Python in limited contexts such as making simple calculations:

#Method 1

((3027)+(100))*5

#Method 2

x = ((3027)+(100))

y = 5

x*yAnother simple use of Python in Shell is checking to see if packages are installed or what version of a package exists.

import pandas

pandas.__version__To exit Python and return to the Shell, type quit() in Python.

Lastly, perhaps one of the most useful implementations of relates to the use of Python scripts run in shell, known as the Python debugger. Suppose you clone a Python Github you would like to adopt but cannot figure out why.

You try to run the script in shell:

python your_broken_cloned_script.py

If you are having trouble debugging the code, consider inserting a debugger. First open the broken script:

atom your_broken_cloned_script.py

Insert the debugger in two steps:

#Import Debugger at Top of Script

import pdb

#Put Debugger Right Before Where the Code Seems to Break

pdb.set_trace()Now save the script and rerun in shell: python your_broken_cloned_script.py

When the script encounters the debugger, the script is halted in place before the error. You will see a version of Python that appears in the shell that you can interact with dynamically. For example, you can have the debugger inside of a loop or iteration to ensure that your loop, it’s inputs, and outputs are working as you expect it.

Coding with Python in Jupyter Notebooks

Jupyter (previously known as IPython) is a dynamic interaction platform that works with the shell and your browser so that you may code and visualize the results in one environment. The closest analog is an RMarkdown document. An important advantage is that you can step by step build your results and analysis, write your text, and visualize the graphs and results without having to constantly re-render the entire document to see updates. This strength is also a weakness as you may inadvertently introduce errors, load data, or create variables in the wrong order, causing errors when trying to replicate.

To launch Jupyter, go to your Shell and type:

jupyter notebook

This will launch your web-browser and Jupyter root location. You will have the option to open or navigate to an existing notebook, or to start a new one.

Once you enter a particular notebook, you can enter code as you would in Python.

Coding with Python in Scripts

A final method of interaction with Python are Python scripts. Similar to RScripts, Python Scripts are a text-based files containing your code, and have the extension “.py”.

These can be edited with any text editor, such as Atom, SublimeText2, or Vim.

Scripts are perhaps most useful when your analysis grows more complex. In practice, all of your work and analysis should not be in one file. If you are building a webscraper to download text files, you may have one file to collect all the target URLs and another script with your speech parsers. Another script may have code to turn the raw text into a database of keywords, phrases, and speech statistics. Once having this data, you will use another script for data analysis.

Depending on your purposes, one script can run other scripts to automate your workflow. Complex functions can be defined in a script and imported for use into another. This type of workflow is cumbersome in Jupyter notebooks, and notebooks contain shortcuts that are not amenable to execution by Python in the Shell.

Basic Data Analysis in Python

As one example of basic data analysis, I have included a Jupyter notebook that covers basic navigation of the Jupyter Notebook, loading data, modifying dataframes in Pandas, and exploring this data using various visualization suites including Matplotlib, Seaborn, and ggplot (for Python).

To access this notebook, do the following in terminal:

git clone https://github.com/jmausolf/Gentle_R_to_Python

cd Gentle_R_to_Python

jupyter notebookThen click the notebook “Coding_with_Python_in_Jupyter_Notebooks.ipynb.”

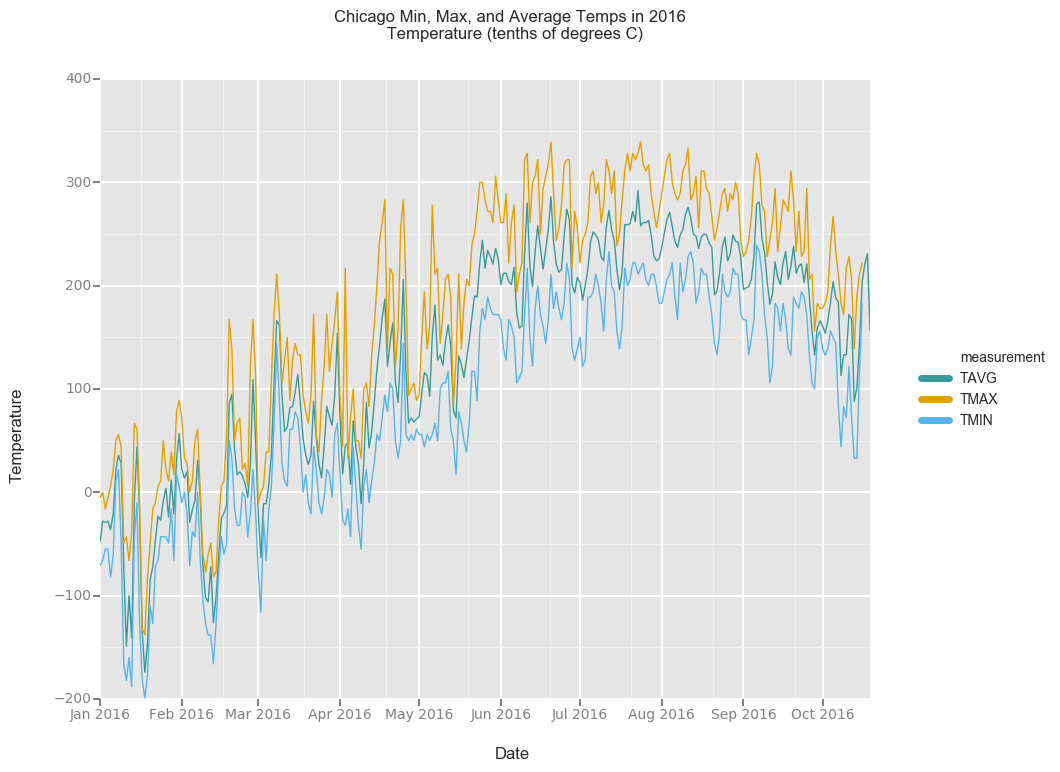

In it, you will learn basis to apply basic Python data analysis and visualization to make figures like this:

Function Basics from R to Python

To illustrate functions in Python and the use of Python scripts, I will illustrate a modified example previously seen in R, the fizzbuzz function. I have modified the script to print the same fizz, buzz, and fizzbuzz responses, but to selectively throw a self-destruct warning countdown timer when a secret key is entered. I call it the fizzbuzzboom.

The original fizzbuzz is defined as follows: If the number is divisible by three, it returns “fizz”. If it’s divisible by five it returns “buzz”. If it’s divisible by three and five, it returns “fizzbuzz”. Otherwise, it returns the number.

First, let’s take a look at this function in R:

fizzbuzzboom <- function(x){

if(x == 524){

delay <- 0.5

print("You have entered the self destruct code...")

Sys.sleep(delay)

print("All your files will be erased...")

Sys.sleep(delay)

print("You have 5 seconds to abort...")

t <- 5+1

Sys.sleep(delay)

while(t > 1) {t <- t-1;

print(t)

Sys.sleep(delay);

}

print("BOOM")

} else if (x %% 5==0 & x %% 3==0){

return("fizzbuzz")

} else if(x %% 5==0){

return("buzz")

} else if(x %% 3==0){

return("fizz")

} else {

return(x)

}

}

fizzbuzzboom(524)In Python, functions are defined similarly, but there are some differences. For starters, here are some basic differences:

- Define a function:

def your_function_name(your_function_arguments): - There are no braces, instead

:are used. - Assign variables using

= if, else if, elsevs.if, elif, else- indentation and white space matter. Improper indents result in errors.

Here is the same function, written in Python:

import time

import argparse

def fizzbuzzboom(input_value, secret_key=524):

"""

The fizzbuzzboom function takes numeric inputs and provides a result.

"""

#Value Checking

try:

x = int(input_value)

pass

except ValueError:

#Handle the exception

print ("Please enter an integer")

return

if x == secret_key:

delay = 0.5

print("You have entered the self destruct code...")

time.sleep(delay)

print("All your files will be erased...")

time.sleep(delay)

print("You have 5 seconds to abort...")

t = 5+1

time.sleep(delay)

while t > 1:

t = t-1

print(t)

time.sleep(delay*2);

print("[*] BOOM")

elif x % 5==0 and x % 3==0:

print("fizzbuzz")

elif x % 5==0:

print("buzz")

elif x % 3==0:

print("fizz")

else:

print(x)

if __name__=='__main__':

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser()

parser.add_argument("number", default=15, type=float, help="submit an integer or float to fizzbuzzboom")

parser.add_argument("-k", "--key", default=524, type=float, help="secret key to intitialize self destruct sequence")

args = parser.parse_args()

print("[*] Calculating the result...")

fizzbuzzboom(args.number, args.key)Note several elements. First, we have to import several libraries for this function to work equivalently in Python. To import a package, instead of library(package) you use import package.

In addition, this function appears much longer because I have added an new option. Whereas the R script could only have different inputs entered and tested within the R environment, the Python version can be called and tested with different arguments in the Shell.

For example, we can run the following in Shell:

python fizzbuzzboom.py 3

[*] Calculating the result...

fizzOr, we can specify a new self-destruct key (default = 524), to initialize the “boom” element of the fizzbuzzboom:

python fizzbuzzboom.py 23 -k 23

[*] Calculating the result...

You have entered the self destruct code...

All your files will be erased...

You have 5 seconds to abort...

5

4

3

2

1

[*] BOOMThis work is licensed under the CC BY-NC 4.0 Creative Commons License.